Ireland's Property News

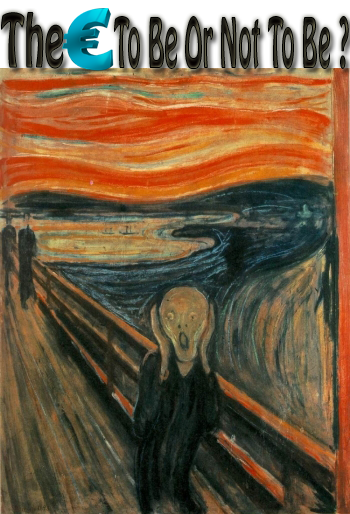

Europe turns against austerity

Europe turns against austerity Measures.

As France's president-elect plans to overhaul the EU fiscal pact and Greek voters turn against austerity, some in bailed-out Ireland are asking if it too has to keep taking the financial pain. Since receiving an 85-billion-euro EU-IMF bailout in November 2010, Ireland has kept its side of the bargain, slashing away at its deficit with its people feeling the sharp end of the cuts.

But with the drive for Europe -wide austerity now in question and France's Socialist president-elect François Hollande vowing to puts more emphasis on a push for jobs and growth, some in Ireland want to renegotiate their terms. The republic holds a referendum on the European Union's fiscal pact on May 31, which is designed to strengthen the euro currency through tighter oversight of public finances.

A "No" vote could give Hollande the platform for a showdown with Germany on renegotiating the deal. "The imposition of austerity across Europe has proven economically toxic and socially corrosive," said David Begg, general secretary of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) umbrella body. "Austerity hasn't worked and it won't work and many people have now woken up to that fact. Across Europe the tide is turning and we are beginning to see the emergence of a new jobs and growth agenda."

Ireland was forced to seek the bailout from the International Monetary Fund and the European Union in 2010 when massive debt and deficit problems left it on the verge of financial collapse. According to The Irish Times newspaper, Hollande's rise to power has given Europe an opportunity for a fresh start politically and economically. "His election sets a trend that could transform European politics," the broadsheet said. "He voices, and will give focus to, the widespread criticism around Europe that budgetary disciplines alone cannot deliver growth and jobs but must be joined by further measures."

The desire for growth to do some of the heavy lifting alongside cutbacks is clear. Irish Deputy Prime Minister Eamon Gilmore said he believed Hollande supported budgetary discipline. But, he added, "what he wants to do, as the Irish government wants to do, is to have that coupled with a growth strategy for Europe." "Ireland does not want to be like Greece," he said, adding that the government would try to achieve economic recovery through investment.

Brigid Laffan, a politics professor at University College Dublin, said the weekend's developments on the continent would be welcomed in Ireland. "Anything that brings growth on the European agenda is a very good thing," she told AFP. "Ireland's an exporting state, so growth in Europe matters to us. The Irish government would say the trend is going in a way that suits us. "There is a reframing going on of what the issues are -- but I guarantee it will not be no austerity. "Any electorate that thinks they don't have to narrow their fiscal deficits over the next 10 years is fooling themselves.

Prime Minister Enda Kenny has a comfortable majority in parliament and could have four years to implement his policy before facing a general election. But for Brian Lucey, a professor of finance and a European economic integration expert at Trinity College Dublin, whatever happens elsewhere, Kenny's government is set in its tracks. "I don't think it makes much of a difference," he told AFP. "This is a government which is cautious, conservative, consensus-forming and won't do anything radical. "They are committed to a policy of 'keep going on as is', and whether the referendum is passed or not, the path up to 2015 is still fairly clear."

The latest survey on April 29 put the "Yes" camp ahead on 47 percent and the "No" on 35 percent -- but that left 18 percent undecided. If Ireland votes "No" this month however, it will only affect Ireland and its access to EU funds -- it will not hold back other member states.

"The days when the Irish banking system posed a contagion threat to the eurozone have gone -- and with it the ability of the Irish government to threaten to use that nuclear card," Lucey said.

Source : AFP .Wednesday 09/05/2012

Comments